Python for Everybody

Exploring Data Using Python 3

Dr. Charles R. Severance

课程简介

Python for Everybody 零基础程序设计(Python 入门)

- This course aims to teach everyone the basics of programming computers using Python. 本课程旨在向所有人传授使用 Python 进行计算机编程的基础知识。

- We cover the basics of how one constructs a program from a series of simple instructions in Python. 我们介绍了如何通过 Python 中的一系列简单指令构建程序的基础知识。

- The course has no pre-requisites and avoids all but the simplest mathematics. Anyone with moderate computer experience should be able to master the materials in this course. 该课程没有任何先决条件,除了最简单的数学之外,避免了所有内容。任何具有中等计算机经验的人都应该能够掌握本课程中的材料。

- This course will cover Chapters 1-5 of the textbook “Python for Everybody”. Once a student completes this course, they will be ready to take more advanced programming courses. 本课程将涵盖《Python for Everyday》教科书的第 1-5 章。学生完成本课程后,他们将准备好学习更高级的编程课程。

- This course covers Python 3.

coursera

Python for Everybody 零基础程序设计(Python 入门)

Charles Russell Severance

Clinical Professor

个人主页

Twitter

University of Michigan

课程资源

coursera原版课程视频

coursera原版视频-中英文精校字幕-B站

Dr. Chuck官方翻录版视频-机器翻译字幕-B站

PY4E-课程配套练习

Dr. Chuck Online - 系列课程开源官网

Object-oriented programming

Python Objects.

We do a quick look at how Python supports the Object-Oriented programming pattern.

Managing larger programs

At the beginning of this book, we came up with four basic programming patterns which we use to construct programs:

- Sequential code

- Conditional code (if statements)

- Repetitive code (loops)

- Store and reuse (functions)

In later chapters, we explored simple variables as well as collection data structures like lists, tuples, and dictionaries.

As we build programs, we design data structures and write code to manipulate those data structures. There are many ways to write programs and by now, you probably have written some programs that are “not so elegant” and other programs that are “more elegant”. Even though your programs may be small, you are starting to see how there is a bit of art and aesthetic to writing code.

As programs get to be millions of lines long, it becomes increasingly important to write code that is easy to understand. If you are working on a million-line program, you can never keep the entire program in your mind at the same time. We need ways to break large programs into multiple smaller pieces so that we have less to look at when solving a problem, fix a bug, or add a new feature.

In a way, object oriented programming is a way to arrange your code so that you can zoom into 50 lines of the code and understand it while ignoring the other 999,950 lines of code for the moment.

Getting started

Like many aspects of programming, it is necessary to learn the concepts of object oriented programming before you can use them effectively. You should approach this chapter as a way to learn some terms and concepts and work through a few simple examples to lay a foundation for future learning.

The key outcome of this chapter is to have a basic understanding of how objects are constructed and how they function and most importantly how we make use of the capabilities of objects that are provided to us by Python and Python libraries.

Using objects

As it turns out, we have been using objects all along in this book. Python provides us with many built-in objects. Here is some simple code where the first few lines should feel very simple and natural to you.

stuff = list()

stuff.append('python')

stuff.append('chuck')

stuff.sort()

print (stuff[0])

print (stuff.__getitem__(0))

print (list.__getitem__(stuff,0))

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/party1.py

Instead of focusing on what these lines accomplish, let’s look at what is really happening from the point of view of object-oriented programming. Don’t worry if the following paragraphs don’t make any sense the first time you read them because we have not yet defined all of these terms.

The first line constructs an object of type list, the second and third lines call the append() method, the fourth line calls the sort() method, and the fifth line retrieves the item at position 0.

The sixth line calls the __getitem__() method in the stuff list with a parameter of zero.

print (stuff.__getitem__(0))

The seventh line is an even more verbose way of retrieving the 0th item in the list.

print (list.__getitem__(stuff,0))

In this code, we call the __getitem__ method in the list class and pass the list and the item we want retrieved from the list as parameters.

The last three lines of the program are equivalent, but it is more convenient to simply use the square bracket syntax to look up an item at a particular position in a list.

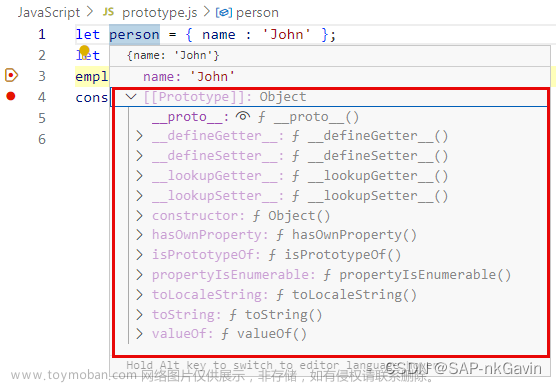

We can take a look at the capabilities of an object by looking at the output of the dir() function:

>>> stuff = list()

>>> dir(stuff)

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__',

'__delitem__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__',

'__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__',

'__gt__', '__hash__', '__iadd__', '__imul__', '__init__',

'__iter__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__', '__mul__',

'__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__',

'__repr__', '__reversed__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__',

'__setitem__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__',

'append', 'clear', 'copy', 'count', 'extend', 'index',

'insert', 'pop', 'remove', 'reverse', 'sort']

>>>

The rest of this chapter will define all of the above terms so make sure to come back after you finish the chapter and re-read the above paragraphs to check your understanding.

Starting with programs

A program in its most basic form takes some input, does some processing, and produces some output. Our elevator conversion program demonstrates a very short but complete program showing all three of these steps.

usf = input('Enter the US Floor Number: ')

wf = int(usf) - 1

print('Non-US Floor Number is',wf)

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/elev.py

If we think a bit more about this program, there is the “outside world” and the program. The input and output aspects are where the program interacts with the outside world. Within the program we have code and data to accomplish the task the program is designed to solve.

A Program

One way to think about object-oriented programming is that it separates our program into multiple “zones.” Each zone contains some code and data (like a program) and has well defined interactions with the outside world and the other zones within the program.

If we look back at the link extraction application where we used the BeautifulSoup library, we can see a program that is constructed by connecting different objects together to accomplish a task:

# To run this, download the BeautifulSoup zip file

# http://www.py4e.com/code3/bs4.zip

# and unzip it in the same directory as this file

import urllib.request, urllib.parse, urllib.error

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import ssl

# Ignore SSL certificate errors

ctx = ssl.create_default_context()

ctx.check_hostname = False

ctx.verify_mode = ssl.CERT_NONE

url = input('Enter - ')

html = urllib.request.urlopen(url, context=ctx).read()

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

# Retrieve all of the anchor tags

tags = soup('a')

for tag in tags:

print(tag.get('href', None))

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/urllinks.py

We read the URL into a string and then pass that into urllib to retrieve the data from the web. The urllib library uses the socket library to make the actual network connection to retrieve the data. We take the string that urllib returns and hand it to BeautifulSoup for parsing. BeautifulSoup makes use of the object html.parser1 and returns an object. We call the tags() method on the returned object that returns a dictionary of tag objects. We loop through the tags and call the get() method for each tag to print out the href attribute.

We can draw a picture of this program and how the objects work together.

A Program as Network of Objects

The key here is not to understand perfectly how this program works but to see how we build a network of interacting objects and orchestrate the movement of information between the objects to create a program. It is also important to note that when you looked at that program several chapters back, you could fully understand what was going on in the program without even realizing that the program was “orchestrating the movement of data between objects.” It was just lines of code that got the job done.

Subdividing a problem

One of the advantages of the object-oriented approach is that it can hide complexity. For example, while we need to know how to use the urllib and BeautifulSoup code, we do not need to know how those libraries work internally. This allows us to focus on the part of the problem we need to solve and ignore the other parts of the program.

Ignoring Detail When Using an Object

This ability to focus exclusively on the part of a program that we care about and ignore the rest is also helpful to the developers of the objects that we use. For example, the programmers developing BeautifulSoup do not need to know or care about how we retrieve our HTML page, what parts we want to read, or what we plan to do with the data we extract from the web page.

Ignoring Detail When Building an Object

Our first Python object

At a basic level, an object is simply some code plus data structures that are smaller than a whole program. Defining a function allows us to store a bit of code and give it a name and then later invoke that code using the name of the function.

An object can contain a number of functions (which we call methods) as well as data that is used by those functions. We call data items that are part of the object attributes.

We use the class keyword to define the data and code that will make up each of the objects. The class keyword includes the name of the class and begins an indented block of code where we include the attributes (data) and methods (code).

class PartyAnimal:

x = 0

def party(self) :

self.x = self.x + 1

print("So far",self.x)

an = PartyAnimal()

an.party()

an.party()

an.party()

PartyAnimal.party(an)

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/party2.py

Each method looks like a function, starting with the def keyword and consisting of an indented block of code. This object has one attribute (x) and one method (party). The methods have a special first parameter that we name by convention self.

Just as the def keyword does not cause function code to be executed, the class keyword does not create an object. Instead, the class keyword defines a template indicating what data and code will be contained in each object of type PartyAnimal. The class is like a cookie cutter and the objects created using the class are the cookies2. You don’t put frosting on the cookie cutter; you put frosting on the cookies, and you can put different frosting on each cookie.

A Class and Two Objects

If we continue through this sample program, we see the first executable line of code:

an = PartyAnimal()

This is where we instruct Python to construct (i.e., create) an object or instance of the class PartyAnimal. It looks like a function call to the class itself. Python constructs the object with the right data and methods and returns the object which is then assigned to the variable an. In a way this is quite similar to the following line which we have been using all along:

counts = dict()

Here we instruct Python to construct an object using the dict template (already present in Python), return the instance of dictionary, and assign it to the variable counts.

When the PartyAnimal class is used to construct an object, the variable an is used to point to that object. We use an to access the code and data for that particular instance of the PartyAnimal class.

Each Partyanimal object/instance contains within it a variable x and a method/function named party. We call the party method in this line:

an.party()

When the party method is called, the first parameter (which we call by convention self) points to the particular instance of the PartyAnimal object that party is called from. Within the party method, we see the line:

self.x = self.x + 1

This syntax using the dot operator is saying ‘the x within self.’ Each time party() is called, the internal x value is incremented by 1 and the value is printed out.

The following line is another way to call the party method within the an object:

PartyAnimal.party(an)

In this variation, we access the code from within the class and explicitly pass the object pointer an as the first parameter (i.e., self within the method). You can think of an.party() as shorthand for the above line.

When the program executes, it produces the following output:

So far 1

So far 2

So far 3

So far 4

The object is constructed, and the party method is called four times, both incrementing and printing the value for x within the an object.

Classes as types

As we have seen, in Python all variables have a type. We can use the built-in dir function to examine the capabilities of a variable. We can also use type and dir with the classes that we create.

class PartyAnimal:

x = 0

def party(self) :

self.x = self.x + 1

print("So far",self.x)

an = PartyAnimal()

print ("Type", type(an))

print ("Dir ", dir(an))

print ("Type", type(an.x))

print ("Type", type(an.party))

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/party3.py

When this program executes, it produces the following output:

Type <class '__main__.PartyAnimal'>

Dir ['__class__', '__delattr__', ...

'__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__',

'__weakref__', 'party', 'x']

Type <class 'int'>

Type <class 'method'>

You can see that using the class keyword, we have created a new type. From the dir output, you can see both the x integer attribute and the party method are available in the object.

Object lifecycle

In the previous examples, we define a class (template), use that class to create an instance of that class (object), and then use the instance. When the program finishes, all of the variables are discarded. Usually, we don’t think much about the creation and destruction of variables, but often as our objects become more complex, we need to take some action within the object to set things up as the object is constructed and possibly clean things up as the object is discarded.

If we want our object to be aware of these moments of construction and destruction, we add specially named methods to our object:

class PartyAnimal:

x = 0

def __init__(self):

print('I am constructed')

def party(self) :

self.x = self.x + 1

print('So far',self.x)

def __del__(self):

print('I am destructed', self.x)

an = PartyAnimal()

an.party()

an.party()

an = 42

print('an contains',an)

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/party4.py

When this program executes, it produces the following output:

I am constructed

So far 1

So far 2

I am destructed 2

an contains 42

As Python constructs our object, it calls our __init__ method to give us a chance to set up some default or initial values for the object. When Python encounters the line:

an = 42

It actually “throws our object away” so it can reuse the an variable to store the value 42. Just at the moment when our an object is being “destroyed” our destructor code (__del__) is called. We cannot stop our variable from being destroyed, but we can do any necessary cleanup right before our object no longer exists.

When developing objects, it is quite common to add a constructor to an object to set up initial values for the object. It is relatively rare to need a destructor for an object.

Multiple instances

So far, we have defined a class, constructed a single object, used that object, and then thrown the object away. However, the real power in object-oriented programming happens when we construct multiple instances of our class.

When we construct multiple objects from our class, we might want to set up different initial values for each of the objects. We can pass data to the constructors to give each object a different initial value:

class PartyAnimal:

x = 0

name = ''

def __init__(self, nam):

self.name = nam

print(self.name,'constructed')

def party(self) :

self.x = self.x + 1

print(self.name,'party count',self.x)

s = PartyAnimal('Sally')

j = PartyAnimal('Jim')

s.party()

j.party()

s.party()

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/party5.py

The constructor has both a self parameter that points to the object instance and additional parameters that are passed into the constructor as the object is constructed:

s = PartyAnimal('Sally')

Within the constructor, the second line copies the parameter (nam) that is passed into the name attribute within the object instance.

self.name = nam

The output of the program shows that each of the objects (s and j) contain their own independent copies of x and nam:

Sally constructed

Jim constructed

Sally party count 1

Jim party count 1

Sally party count 2

Inheritance

Another powerful feature of object-oriented programming is the ability to create a new class by extending an existing class. When extending a class, we call the original class the parent class and the new class the child class.

For this example, we move our PartyAnimal class into its own file. Then, we can ‘import’ the PartyAnimal class in a new file and extend it, as follows:

from party import PartyAnimal

class CricketFan(PartyAnimal):

points = 0

def six(self):

self.points = self.points + 6

self.party()

print(self.name,"points",self.points)

s = PartyAnimal("Sally")

s.party()

j = CricketFan("Jim")

j.party()

j.six()

print(dir(j))

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/party6.py

When we define the CricketFan class, we indicate that we are extending the PartyAnimal class. This means that all of the variables (x) and methods (party) from the PartyAnimal class are inherited by the CricketFan class. For example, within the six method in the CricketFan class, we call the party method from the PartyAnimal class.

As the program executes, we create s and j as independent instances of PartyAnimal and CricketFan. The j object has additional capabilities beyond the s object.

Sally constructed

Sally party count 1

Jim constructed

Jim party count 1

Jim party count 2

Jim points 6

['__class__', '__delattr__', ... '__weakref__',

'name', 'party', 'points', 'six', 'x']

In the dir output for the j object (instance of the CricketFan class), we see that it has the attributes and methods of the parent class, as well as the attributes and methods that were added when the class was extended to create the CricketFan class.

Summary

This is a very quick introduction to object-oriented programming that focuses mainly on terminology and the syntax of defining and using objects. Let’s quickly review the code that we looked at in the beginning of the chapter. At this point you should fully understand what is going on.

stuff = list()

stuff.append('python')

stuff.append('chuck')

stuff.sort()

print (stuff[0])

print (stuff.__getitem__(0))

print (list.__getitem__(stuff,0))

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/party1.py

The first line constructs a list object. When Python creates the list object, it calls the constructor method (named __init__) to set up the internal data attributes that will be used to store the list data. We have not passed any parameters to the constructor. When the constructor returns, we use the variable stuff to point to the returned instance of the list class.

The second and third lines call the append method with one parameter to add a new item at the end of the list by updating the attributes within stuff. Then in the fourth line, we call the sort method with no parameters to sort the data within the stuff object.

We then print out the first item in the list using the square brackets which are a shortcut to calling the __getitem__ method within the stuff. This is equivalent to calling the __getitem__ method in the list class and passing the stuff` object as the first parameter and the position we are looking for as the second parameter.

At the end of the program, the stuff object is discarded but not before calling the destructor (named __del__) so that the object can clean up any loose ends as necessary.

Those are the basics of object-oriented programming. There are many additional details as to how to best use object-oriented approaches when developing large applications and libraries that are beyond the scope of this chapter.3

Glossary

attribute

A variable that is part of a class.

class

A template that can be used to construct an object. Defines the attributes and methods that will make up the object.

child class

A new class created when a parent class is extended. The child class inherits all of the attributes and methods of the parent class.

constructor

An optional specially named method (__init__) that is called at the moment when a class is being used to construct an object. Usually this is used to set up initial values for the object.

destructor

An optional specially named method (__del__) that is called at the moment just before an object is destroyed. Destructors are rarely used.

inheritance

When we create a new class (child) by extending an existing class (parent). The child class has all the attributes and methods of the parent class plus additional attributes and methods defined by the child class.

method

A function that is contained within a class and the objects that are constructed from the class. Some object-oriented patterns use ‘message’ instead of ‘method’ to describe this concept.

object

A constructed instance of a class. An object contains all of the attributes and methods that were defined by the class. Some object-oriented documentation uses the term ‘instance’ interchangeably with ‘object’.

parent class

The class which is being extended to create a new child class. The parent class contributes all of its methods and attributes to the new child class.

-

https://docs.python.org/3/library/html.parser.html ↩︎

-

Cookie image copyright CC-BY https://www.flickr.com/photos/dinnerseries/23570475099 ↩︎文章来源:https://www.toymoban.com/news/detail-725756.html

-

If you are curious about where the

listclass is defined, take a look at (hopefully the URL won’t change) https://github.com/python/cpython/blob/master/Objects/listobject.c - the list class is written in a language called “C”. If you take a look at that source code and find it curious you might want to explore a few Computer Science courses. ↩︎文章来源地址https://www.toymoban.com/news/detail-725756.html

到了这里,关于Chapter 15: Object-Oriented Programming | Python for Everybody 讲义笔记_En的文章就介绍完了。如果您还想了解更多内容,请在右上角搜索TOY模板网以前的文章或继续浏览下面的相关文章,希望大家以后多多支持TOY模板网!